By Colleen Jones

Published: August 3, 2009

To know your content is to love it. Content analysis is an essential part of many UX design projects that involve existing content. Examples of such projects include migrating a Web site to a new platform or design, merging multiple Web sites into one, or assessing Web content for reuse in a new channel. Just as you cannot nurture a garden without regularly inspecting its plants and flowers, you cannot take proper care of your content without looking at it closely. You must become familiar with your content to judge whether it’s effective, understand how it relates to other content, make decisions about how to use or format it, identify opportunities for improving it, and more. Content analysis, though time consuming, is fruitful, because your efforts provide the following benefits:

- Content analysis results in a clear, tangible description of your content—which clients and stakeholders can perceive as nebulous—whether expressed in text or visually.

- Content analysis provides the foundation for comparing existing content with either user needs or competitor content, letting you identify potential gaps and opportunities. [1]

- Content analysis offers insights that help you make decisions about your content more easily—for example, what to prioritize.

- Content analysis can reveal themes, relationships, and more.

In this column, I’ll walk you through a content analysis—and offer tips and tricks along the way that will help make your next content analysis more effective.

Start with the Roots: A Content Inventory

Before you can analyze your content, you must identify what content there is. For two useful perspectives on doing content inventories, see these essays:

- “Doing a Content Inventory (Or, a Mind-Numbingly Detailed Odyssey Through Your Web Site)”

[2]

[2] - “The Content Inventory Is Your Friend”

[3]

[3]

Ultimately, a content inventory results in a detailed spreadsheet that, at a minimum, lists the existing content.

Weed Out the ROT

A common method of analyzing content uses the ROT (Redundant, Outdated, Trivial) set of heuristics. Often an analysis using these heuristics is part of a broader content analysis, as the abovementioned essays note. This important analysis gets rid of the obviously bad content.

The problem? Many people end their content analyses there. For me, a ROT analysis is just the beginning. While it tells you what content is stale or woefully unimportant, it does not tell you what content is mediocre, inappropriate, inconsistent, or off brand. To reveal more useful insights about your content—and consequently, make better decisions about your content—you must take content analysis a step further.

Expand Your Tool Set, Then Work Away

Just as, to truly care for a garden, you need more than a weedeater, you need more than the ROT heuristics to analyze content effectively. In hisBoxes and Arrows article “Content Analysis Heuristics,”![]() Fred Leise offers the following helpful heuristics [4], with a focus on information architecture:

Fred Leise offers the following helpful heuristics [4], with a focus on information architecture:

- collocation

- differentiation

- completeness

- information scent

- bounded horizons

- accessibility

- multiple access paths

- appropriate structure

- consistency

- audience relevance

- currency

In a recent UXmatters column, “Toward Content Quality,” I shared some basic characteristics of content quality, with an eye toward turning them into heuristics: [5]

- usefulness and relevance

- clarity and accuracy

- completeness

- influence and engagement

- voice and style

- usability and findability

Other important, basic characteristics include some of those noted in the content inventory essays I mentioned earlier:

- type

- format—for example, text, PDF, or image

- intended audience

- business or user priorities

Plus, there are numeric ratings of quality or effectiveness you can use to judge whether content meets a heuristic.

Occasionally, you might want to add a characteristic to address a specific project issue, challenge, emphasis, or need. If there is a content characteristic you want to track or understand better, you need to include it in your content analysis.

Including every single heuristic or characteristic I just listed would make your content analysis extremely time consuming. You should select the combination of heuristics and characteristics that make the most sense for your project.

I recently decided to use a combination of some of these heuristics—taking some from each set—for a project that involved migrating and merging several disparate Web sites. After analyzing part of one Web site, I realized that a couple of my selections were not applicable or useful, so I dropped them.

Figure 1—Part of a content analysis spreadsheet

When I finished, I found the results quite helpful. I’ll give you a glimpse of them in the next section.

See the Content Forest Thanks to the Trees

Once you’ve completed a content analysis, you have the ability to paint an overall picture of your content’s current state. Specifically, you can synthesize your analysis into useful descriptions and insights. You can also identify examples of key content issues. By synthesizing your analysis and developing descriptions, insights, and illustrative examples, you can gain information that is valuable in making strategic decisions about your content.

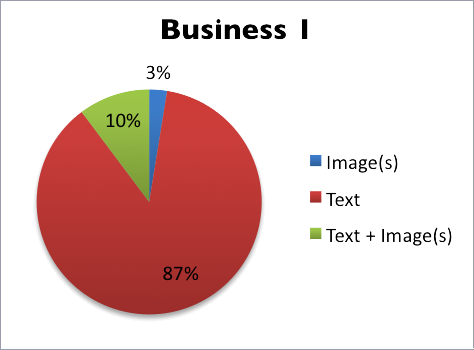

Content Descriptions

Stakeholders and clients won’t always look at your ponderous spreadsheets—even if they should—but they will pay attention to useful visuals you’ve coupled with smart insights. Thanks to the magic of spreadsheets, you can create pivot tables, then graphic depictions of your content. Figure 2 shows a pie chart I created recently for a content analysis, showing the content formats that were present on a Web site.

Figure 2—Pie chart showing types of content on pages

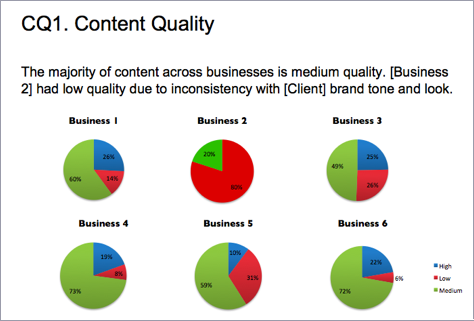

For a project that involved assessing the content of multiple Web sites, in preparation for integrating them, I had an easy basis for comparison, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3—Pie charts comparing content quality across several Web sites

Such depictions of data also provide a way of evaluating existing content in light of user needs or comparing your content to that on competitor Web sites and identifying gaps.

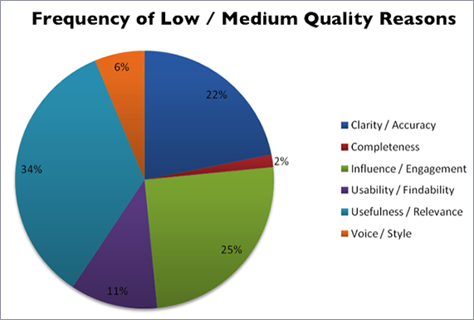

In a recent post to the Content Strategy Google Group, Kristina Halvorson noted that content auditing involves both quantitative and qualitative elements. I wholeheartedly agree. While the charts I’ve shown you so far focus mainly on quantitative descriptions, I’ve also used charts for qualitative ratings. Figure 4 shows a pie chart that illustrates the reasons for a content-quality rating.

Figure 4—Pie chart depicting reasons for a content-quality rating

To help bring these qualitative ratings and the reasons for them to life, I illustrated them with specific examples.

Examples of Content Issues

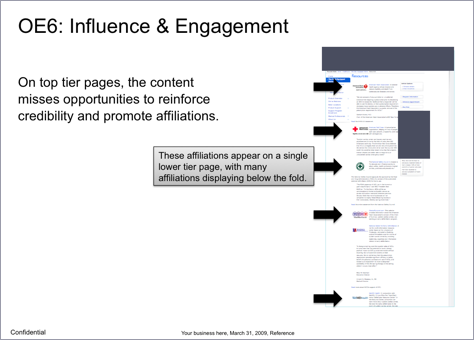

If you tell a client or stakeholder their content has issues, they understandably want to know what issues and why they are issues and to see examples of the issues. A content analysis lets you flag and refer to specific examples of content problems—for example, different types of problems or anything else you want to illustrate. Consequently, you can easily snag a screen capture for a presentation or pull up a Web page during a meeting. Figure 5 shows a slide that depicts one of my favorite issues—missing an opportunity to influence.

Figure 5—Missing an opportunity to influence

When meeting with a client or stakeholder, you can show particular content examples and quickly address many issues—even on multiple Web sites. I find that, not only does this help you to be efficient, it also assures a client or stakeholder that their content is in good hands. It’s surprising how often I point out examples a client or stakeholder is notaware of or had forgotten. But without my content analysis, I would have found it difficult to do this effectively.

In Closing: Get Out of It What You Put into It

Content analysis reliably gives you returns on your investment. You get back what you put into it. While choosing the right heuristics for your content analysis and synthesizing them properly takes practice and a bit of flair, the vision you gain makes your effort worthwhile.

In my opinion, an experienced UX professional is capable of assessing content more efficiently, thoroughly, and sensitively than someone with little experience. Proceed with caution if you turn a green intern completely loose on your content analysis, because the results you get are unlikely to help you see beyond the trees. Effective analysis and strategic thinking take maturity of vision.![]()